Miranda Article

Many of us have heard those statements, but few of us fully understand them.

On March 13, 1963, police arrested Ernesto Miranda on charges of rape and kidnapping after a witness identified him in Phoenix, Arizona. Following his arrest, the police brought Ernesto Miranda in for questioning on a larceny charge. During his two-hour interrogation, police did not advise Miranda of his constitutional rights to an attorney or to remain silent. Nonetheless, Miranda signed a written confession affirming knowledge of these rights and admitting to the crimes. On June 27, 1963, Miranda was convicted of rape, kidnapping, and robbery.

Miranda appealed his conviction to the U.S. Supreme Court, which reviewed the case in 1966. The Supreme Court, in a 5-4 decision written by Chief Justice Earl Warren, ruled that the prosecution should not have introduced Miranda’s confession as evidence because the police failed to first inform Miranda of his right to an attorney and his right against self-incrimination. Today, the Miranda Rights remain, in the words of Chief Just Earl Warren, “the essential mainstay” of our legal system.

To commemorate the sixtieth-year anniversary of the arrest of Ernesto Miranda, and the start of a three-year saga that culminated in the Supreme Court case of Miranda v. Arizona, Fayetteville Technical Community College filmed a historical reenactment of the key moments in the Miranda ordeal.

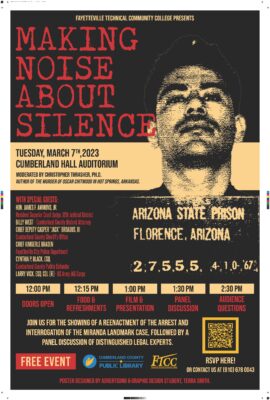

Please join us in the Cumberland Hall Auditorium (2211 Hull Road) at Fayetteville Technical Community College (FTCC) on March 7 from 12:00 – 3:00 for “Making Noise About Silence,” the world premiere of FTCC’s educational film about the Miranda decision. After playing the short film, legal and law enforcement experts from our community will share their thoughts on the Miranda case. Members of the panel will then answer audience questions.

What you learn at this event might be the only thing that keeps you, or someone you love, out of jail.

The event is open and free to the public, but space is limited. Please RSVP today to reserve your seat.

Guest Speakers

Hon. James F. Ammons, Jr., Resident Superior Court Judge, 12th Judicial District

Chief Deputy Casper “Jack” Broadus, III, Cumberland County Sheriff’s Office

Billy West, Cumberland County District Attorney

Cynthia P. Black, Esq., Cumberland County Public Defender

Larry Vick, Esq. Col (R), US Army JAG Corps

Chief Kimberle Braden, Fayetteville City Police Department

Miranda Script

This short film is an interpretation of actual events that took place on March 13, 1963.

In Miranda v. Arizona, the United States Supreme Court held that custodial interrogation of an individual must be accompanied by instructions that the person has the right to remain silent, that any statements made can be used against the person, and that the individual has the right to counsel. If these safeguards are absent, statements made will be inadmissible in court. These constitutional rights have since become known as the Miranda Rights.

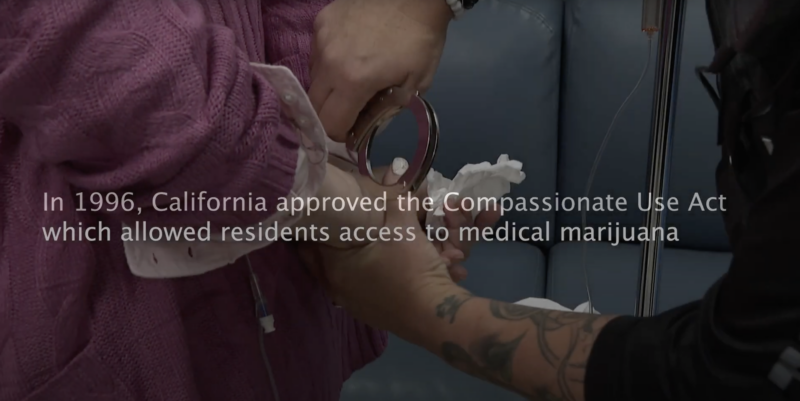

On March 13, 1963, police arrested Ernesto Miranda on charges of rape and kidnapping after a witness identified him in Phoenix, Arizona.

Following his arrest, the police brought Ernesto Miranda in for questioning on a larceny charge. During his two-hour interrogation, police did not advise Miranda of his constitutional rights to an attorney or to remain silent. Nonetheless, Miranda signed a written confession affirming knowledge of these rights and admitting to crimes.

Ernesto Miranda asked the court not to accept his written confession into evidence. The court denied his request, and the confession was presented as evidence during his trial. On June 27, 1963, Miranda was convicted of rape, kidnapping, and robbery. Judge McFate sentenced Miranda to a maximum of fifty-five years in prison. Miranda’s lawyer, Alvin Moore, appealed the case to the Arizona Supreme Court, which reaffirmed the lower court’s decision, holding that the police had not violated Miranda’s constitutional rights in procuring a confession without the presence of a lawyer.

Miranda appealed his conviction to the U.S. Supreme Court, which reviewed the case in 1966. The Supreme Court, in a 5-4 decision written by Chief Justice Earl Warren, ruled that the prosecution should not have introduced Miranda’s confession as evidence because the police failed to first inform Miranda of his right to an attorney and his right against self-incrimination.

In the years after Miranda, the U.S. Supreme Court and other lower courts further clarified that members of law enforcement must advise suspects who are being questioned while in custody, without the option to leave, of their “Miranda Rights”. Today, the Miranda Rights remain, in the words of Chief Just Earl Warren, “The Essential Mainstay” of our legal system.

You have the right to remain silent.

You have the right to remain silent.